Getting Willie straight is not a particularly easy chore. On the field and to

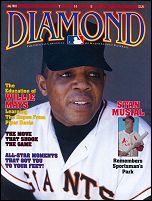

Nearly 28, Willie Mays has grown into a man..

IT MAY SEEM incredible to those of us who cherish

the sweet bloom of youth – and we are many – but the time has come to face

the fact that Willie Mays is a grown-up man. The years have flowed

along, the hits and runs and putouts have inscribed themselves into the

record books, and in a month the Say, Hey Kid will be 28 years old.

Not counting the time he did a bit of soldiering for Uncle Sam, Willie

has now been doing his stuff for the Giants for about six seasons.

He has been playing pro ball for 12 years; he has married and has a family

and, as the pictures on the preceding pages show, he has established a

way of life for himself far removed from his native Birmingham and the

Harlem flat where he started his big league career. In brief, it’s

time to take another look at Willie Mays, hub and mainstay of the Giants’

baseball team.

| For some reason probably connected with man’s reluctance

to let go of his ebullient, few have paused to do this. Nearly everybody

persists in regarding Willie as the same chortling, happy-go-lucky, amusingly

naïve youngster who brought a new light to the Polo Grounds back in

1951. Actually, the mature Willie doesn’t believe he was ever quite

that damp behind the ears. He feels that a lot of the stories about

him were moonshine. In the main they were amusing, colorful and highly

flattering moonshine, and Willie is now wise enough and modest enough to

realize they helped make him rich and famous, so he isn’t resentful.

“It does seem, though” he said recently, “that nobody ever got me quite

straight.”

Getting Willie straight is not a particularly easy chore. On the field and to |

Nearly 28, Willie Mays has grown into a man.. |

His fellow Giants certainly have no delusions about Willie. Nowadays he seldom indulges in the frisky antics which caused some impressionable scribes to imagine that he was one of the greatest natural zanies to prance on the scene since Uncle Wilbert Robinson ran a nuthouse in Brooklyn. Willie rarely clowns in a pepper game. He loftily eschews gleeful locker-room pranks. It’s unusual for him to provoke a spirited jeering and exchange with one of his benchmates. Nor, except for a few oldtimers, notably big Hank Sauer, does anybody rag Willie. But there is no question about Willie’s still being the sparkplug of the Giants. He hustles as energetically as any of his teammates and bustles more thrillingly than most of them put together. The big difference is that Willie is now the star instead of a fondly regarded mascot. The Giants know it and Willie knows it.

Willie may be short on words but he is a genius at another form of communication. When he scampers onto a ball field and begins using the heroic muscle that make him look as if he were designed by Michelangelo or Al Capp, everybody gets the message. H.R.H. the Duke of Windsor, for example, can hardly be called an excitable type. Yet as he sat in the Arizona sun not so long ago, watching an exhibition game between the Indians and the Giants, the Duke, a man who even held his royal aplomb throughout the historic rhubarb over his marriage, suddenly swallowed hard, sat bolt upright, chewed fiercely on his pipestem and in general showed the agitation peculiar to an oldtime Coogan’s Bluff slob. What cracked the royal demeanor was, of course, the familiar spectacle of Willie poling a ball out of the park and apparently into orbit.

Jolting a royal duke with the special brand of baseball excitement he generates pleases Willie, but not excessively. He is a democratic fellow, and, barring catastrophe, probably will tamper with the blood pressure of thousands of ordinary men and women and even innocent children at least once in each of the games he plays this year. He will do it, as everybody knows, by pulling off what can loosely be described as The Play – that one magical performance which lingers in the memory and demands to be recalled at length and with gesture long after more mundane details of the game have been forgotten. But Willie will do it, as always, with a difference.

For one thing, when Willie is on the field nobody can be quite sure when The Play will come. Unlike most diamond heroes, past or present, Willie is not confined to one predictable and carefully nurtured talent. The Play might come when he transforms his 185 pounds and 5 feet 11 inches into a spike-tipped projectile and steals second. He might pull it off by swinging his 34-ounce 35-inch bat like a buggy whip and driving a ball past the point of no return. Chances are always excellent that he will do it by preposterously fielding a ball which by rights shouldn’t have been caught. Again he might do it by skidding to an off-balance halt deep in center field and firing a ball unerringly to home plate. Willie has done all of these things spectacularly. He has done them too often to recount.

“I always try to do something new,” is the way Willie, somewhat gropingly, tries to explain it. “I don’t try to do what the other fellow does. People come to ball games to see fellows do something different.”

Now and then attempts have been made to leave the impression that the mature Willie’s teammates consider him a showboat. To a man they deny it. The truth is, just as they know he is not a comedian, the know that nobody plays ball as well as Willie does just on instinct alone. The are aware how hard Willie works, not merely to improve his ballplaying, but to add an extra dash of showmanship to all his actions. One of the things Willie thinks nobody has ever got quite straight is that he is not simply a natural-born ballplayer. “I pick up something that looks different and I practice up on it,” Willie explains. “Like the basket catch I use. It took me about a year, while I was in the Army, to learn to do it well.”

Willie broods when he makes an error. “It makes me feel bad if I don’t hit or if I let the pitcher down by making a bad play. It worries me real bad. I don’t cry or nothing like that, but I feel like it sometimes because I feel like I let the other fellows down.”

Most of the Giants do sometimes show a cynical, if appreciative, attitude toward Willie’s flair for dramatics. For instance, when a fast pitch hit the handle of Willie’s bat in an exhibition game with the Red Sox this spring, there were snorts and guffaws in the dugout when he threw himself to the ground and writhed convulsively. Somebody made the standard comment: “He oughta get an Oscar for that.” A few days later, when Willie shuffled into the dugout after going to the hospital to be treated for a gash in the right leg received in a sliding accident, everybody grinned and Coach Salty Parker cracked, “What are you trying to pull now, Willie?” The grins faded when Willie said cheerfully, “Man, I got 35 stitches in this leg.” Fortunately, the wound was not serious despite all the sewing.

As the biggest Giant of them all, drawing the biggest salary ever paid in Giant history, probably $75,000 a year, Willie naturally awes some of the newcomers. He pays them the compliment of treating them like everybody else, and also of overlooking their gaucheries. This was illustrated recently when a young and nameless pitcher, up for a tryout, sauntered out to face Willie in batting practice. He was overly nonchalant, so pokerfaced that it was screamingly apparent that he was scared to death to find himself facing the great Mays.

“You got a curve?” Willie called.

“Yeah,” the youngster said. He heaved the ball. Willie smacked it over the fence. The pitcher didn’t look up.

“You got something else?” Willie called.

“Yeah,” the youngster grunted. He heaved another ball. Willie smashed in solidly and it sizzled three feet off the ground, straight as a bullet, and smacked the pitcher in the right leg a little above the knee. It happened so incredibly quickly that he didn’t have time to lower his glove. The crack of the bat and the solid sound of ball meeting flesh in a paralyzing blow almost blended together. A sudden silence fell over the players clustered behind the batting cage. Willie lowered his bat and looked solicitous. But the young pitcher did not wince, grimace or even look down at his leg. Apparently he was manfully determined to show that getting his leg almost knock off with a ball didn’t faze him in the slightest.

After a moment, Hank Sauer, who had been watching, laughed, “You’ll have to hit it harder than that, Willie. That boy won’t even have a bruise next week this time.”

Willie looked with seeming bewilderment at the young pitcher, nonchalantly toeing up for another pitch. A grin began to tug at the corners of Willie’s mouth, but diplomatically, he kept it from spreading.

Being the star of any team carries with it some special privileges. They are not defined because they depend on the individual star and what the traffic will bear. So far the only privilege Willie has claimed is a room to himself when the Giants are on the road. He invariably is among the first to arrive at the ball park and among the last to leave. Sportswriters who follow the Giants around are agreed that Willie is one of the hardest-working players they have ever seen. There was considerable indignation in their ranks when word got around toward the end of the 1956 season that Willie had been fined $25 for not hustling on a play in a game in St. Louis. In the play in question Willie had popped up but didn’t run because the thought the ball was going foul. It was caught in front of the plate. All set to whip up a cause célèbre because a hard-working player had been fined for not hustling when all he was guilty of, if anything, was an error of judgement, the scribes bearded Manager Bill Rigney. Yes, said Rigney, the report was true. Willie had returned to the dugout and said, “I should be fined for that.” Whereupon Rigney said, “That’s right. You are fined. Twenty-five bucks.” Then Rigney put the matter to rest. “I have,” he announced, “withdrawn the fine, because Mays is the hustlingest guy in the world.”

Willie had no comments on the fine at all. He has clear-cut opinions on a player-manager relationship. “A manager should tell a player what he wants him to do. If the player don’t do it, then the manager should take some of his money away from him. I think that’s the quickest way to get a player to do what he should.” Willie looks blank when someone comments on how hard he hustles. “I never can understand how some players are always talking about baseball being hard work. To me, it’s always been a pleasure, even when I feel sort of draggy after a double-header.”

In Willie’s life there isn’t a time he can remember that wasn’t dominated by baseball. He was born on May 6, 1931, in Westfield, Alabama, a grimy little steel-mill town near the outskirts of Birmingham. Willie’s father, Willie Sr., worked in the tool room of the mill and played in the outfield on the mill’s baseball team. Nicknamed “Kitty Cat” because of his fast hands, the elder Mays was also a former outfielder and lead-off hitter for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro National League. “Willie,” his father has related, “was almost born on a ball diamond. There was a ball field right across the street from where we lived. When Willie was 14 months old I gave him a rubber ball. I used to come home from the steel mill, and every afternoon I’d roll that rubber ball across the floor to Willie – oh, 30 or 40 times – until I’d get tired. Willie never got tired. As soon as I stopped rolling the ball, he’d cry.”

WHEN Willie was 3, he and his father would go over to the ball diamond and play catch in the afternoons. “But by the time Willie was 6,” his father said, “I’d come home from work and catch him across the street on the diamond all alone, playing by himself. He’d throw the ball up and hit it with the bat and then run and tag all the bases – first, second and third – and then when he got home, he’d slide. He learned that from watching me. I showed him how to slide.”

Before Willie reached school age, his mother and father separated, and Willie went to live with an aunt, Mrs. Sarah Mays. Willie still thinks of Sarah Mays as his mother, and her death in 1954 dealt him a crushing blow. His real mother died in 1953 while giving birth to her 10th child by her second marriage.

Some of the nonsense written about Willie concerns his childhood. “It makes me laugh to read some stories about how I picked cotton as a boy or worked in one of the mills around home,” he says. “All I ever did since I was 6 was play ball, except for when I was in the Army and one other time. That was when I was in 15, and got a job in a café in Birmingham washing dishes. Folks there treated me grade-A, but I quit after one week.”

Stories which tell of Willie’s poverty as a child are also misleading. Sarah Mays’s home, the only home Willie remembers, is in Fairfield, another small industrial town adjacent to Birmingham, on a height overlooking the steel mills. It is neat and substantial and considerably better than the homes of some steel workers in the community, white and Negro. Willie’s father, who never remarried, lived a few blocks away. He and most of the other menfolks in Willie’s family worked in the mills and drew the prevailing union wage. Willie’s childhood may not have been bountiful but he never missed a meal and was adequately clothed and attended school regularly.

Willie, admittedly, did not have scholarly learnings. “All the time my algebra teacher was saying X equals how much?” I was thinking about the next ball game,” he has confessed. To which his father says: “I never saw a boy who loved baseball the way Willie always did.” The youngster was always on hand when his father played in the outfield in the local Industrial League games. Whenever possible he even accompanied the team on its short trips to play in other communities. It was some time before Willie realized his father was paid money for playing ball. “I remember the biggest surprise of my life was that day I found out folks paid him money for it,” he says. “That seemed to me just about the nicest idea that anyone ever thought up.”

By the time Willie was 10 he was playing ball with 15-year-olds. “Even then he never did throw the ball the way other boys did,” his father recalls. “He threw that kind of underhanded throw. He got that throw from rolling that ball when he was real young.” At 14, Willie was excelling as a pitcher and earning a few dollars with a semipro steel-mill team. He was also attending Fairfield Industrial High School and taking a trade course in pressing and cleaning. One advantage of the course was that Willie had access to the school’s equipment and could do his own clothes free of charge. To this day he seems to feel a real pain when he sees wrinkled clothing. The slacks and sports jackets in his bulging wardrobe are impeccably pressed, and he even wears creases in his uniform pants.

Willie’s high school did not have a baseball team, so Willie – who for some reason nobody can remember had acquired the nickname of “Buckduck” – took a fling at football and basketball. He make such a reputation as a fullback that for a brief spell he considered concentrating on football and trying to win a college scholarship. But baseball kept beckoning and, besides, college wasn’t much of an attraction to Willie, free or otherwise. When he was 16 his father settled the matter by taking him around to meet an old friend, Lorenzo (Piper) Davis, manager of the Black Barons in Birmingham. Davis gave Willie a tryout and promptly signed him as an outfielder. Part of the agreement was that Willie would continue attending high school. It wasn’t difficult for the Barons’ management and Willie’s principal to work out a program which permitted him to be excused from school when he was needed to play ball.

Willie’s single flaw at the time was his hitting. Davis promised him an extra $5 a month if he would hit .300, but Willie never collected. “He stood a little too close to the plate,” Davis said. “He kept thinking that all the pitcher were trying to hit him, but he was just crowding.”

If reports can be believed, most big league scouts got wind of Willie almost from the time he put on a Barons’ uniform. Harry Jenkins, once a director of farm personnel for the Boston Braves, has revealed that he first started keeping and eye on Willie when he was only 13. It is a fact that the Braves made an offer for Willie shortly after the Barons signed him. They offered $7,500 for Willie’s contract and $7,500 more if he made good. They could not, of course, sign Willie until he graduated. The Chicago White Sox were also waiting for Willie to finish school. But while they were waiting, a couple of Giants scouts, Ed Montague and Bill Harris, arrived in Birmingham to look over First Baseman Alonzo Perry. They decided that Perry wouldn’t do, but after the game Montague went directly to a telephone and called New York. “I saw a young kid of an outfielder I can’t believe,” he said. “He can run, hit to either field and has a real good arm. Don’t ask any questions. You’ve got to get this boy.”

Montague’s enthusiasm was infectious. He was told not to leave Birmingham until he had signed Willie. Montague offered the Barons a flat $10,000 for Willie’s contract, which took care of the Braves’ proposition. The day after Willie graduated in June 1950, Montague showed up at his home and offered him $2,000 to sign with the Giants. Willie and his father said that wasn’t enough; they wanted $6,000. Without dickering, Montague immediately telephoned Horace Stoneham and explained the situation. Stoneham said to give Willie what he wanted.

THIS story indicates that Willie has never underestimated his value. Now that he is pushing 28, one of the things he would like to set straight is the persistent old tale that he loves to play baseball so much that he doesn’t care what he is paid. “Maybe that makes a good story,” Willie said, “but I never said anything like that to Mr. Stoneham. If a fellow hits .340 or something like that year after year and plays good ball, he sure can say he’s worth whatever he can get.”

Willie was 19 when he reported to the Giants’ farm club in Trenton, N.J. By midseason it was apparent he was already too good for Class B ball. He was allowed to season until the next year, however, and then brought up to Minneapolis and Triple-A ball. That year Willie couldn’t do anything poorly. He hit a fancy .477 and still worked overtime trying to improve his hitting. A devoted admirer of Joe DiMaggio, he spent hours practicing Dimag’s stance, copying his swing. As for his fielding, then, as now, he didn’t have to worry about it. If it was humanly possible to catch a ball, Willie would catch it. Frequently, as Minneapolis discovered, he did it when it wasn’t humanly possible. Minneapolis had never seen a ballplayer like Willie. On the probably valid assumption that it never would again, fans made the most of the opportunity. To this day some Minneapolis fans remove their hats and grow misty-eyed when the name of Willie Mays is mentioned.

Naturally, news of this brilliant young busher reached the ears of Leo Durocher, who was wallowing noisily in a slough of despair and managing a team laughingly called the Giants. Durocher asked for Mays to be brought to New York. Horace Stoneham refused. “He’s not ready for the majors,” he said. “Anyway, he’s due to go into the Army at any minute.”

The Giants lost 11 games in a row. Durocher screamed incessantly for Mays. Finally, Stoneham capitulated. But to prevent a mass demonstration in Minneapolis, he took the unprecedented step of inserting ads in the local papers which began by apologizing for taking Mays away and concluding with this ringing plea for fair play: “Mays is entitled to his promotion, and the chance that he can play major league baseball. It would be unfair to deprive him of the opportunity he earned with his play.”

THERE is still no logical and completely satisfactory explanation of how 20-year-old Willie Mays wrought such magic with the Giants back in 1951. But it is a fact that with his arrival a bunch of unhappy and dispirited players, united only in that they wore similar uniforms, suddenly became a team, one of the sweetest ball teams in modern history. Probably Durocher deserves more credit than he is given. From the day he first clapped eyes on Willie he was electrified by his potentialities. To anyone who would listen he predicted that Willie would go down in baseball history as one of the greatest players of all time. Durocher loved to hear Willie talk. Willie was his lucky talisman, his mascot, his jester and his ward. Willie relaxed him. Before a game, when he was normally tense and worried, he would start a pepper game with Willie and in a few minutes be gamboling like a rookie. Durocher’s enthusiasm was contagious. The team liked Willie and he became their mascot also.

Willie still adores Durocher. “Leo never steered me wrong – ever,” he says. “He was good to me and I liked him the same way I do my father. I miss him all right, but a man has got to learn to look after himself in baseball.”

But if Willie was good for Durocher, it also is true that Durocher was good for Willie. In his first few games with the Giants, the new hope was a dismal flop. In 26 times at bat he came up with just one hit, a lone home run.

One night after a game, Durocher came into the clubhouse and found Willie sitting in front of his locker and crying. Leo put his arm around him and asked, “What’s the matter, son?”

“Oh, Mister Leo,” Willie said. “I can do you any good. I can’t do you any good. I can’t get a hit. I can’t win you any ballgames. And I know you’re gonna send me back to Minneapolis.”

“Look, Willie,” Leo said, “this ball game’s over. Tomorrow’s another day. And don’t you worry about me sending you back to Minneapolis. You’re the best center fielder – you’re the best ballplayer – I’ve ever seen. Now you go home and get a good night’s sleep.”

That was the turning point for Willie. The next day, against the Pirates, he lined a single to center his first time up and followed that later with a triple that brought in two runs. The Giants beat the Pirates 14-3, and Willie went on to finish the season with 20 home runs, a batting average of .274 and the title of Rookie of the Year. Furthermore, he sparked the rejuvenated Giants to their first pennant since 1937.

When Willie’s draft call came in May 1952 he applied for deferment on grounds that he was the principal support of his mother and nine half-brothers and sisters. It was refused. The Army also ignored the fact that he flunked his pre-induction aptitude test. He spent most of his 21 months in the Army at Fort Eustis, Virginia, attached to the transportation branch. But Willie admits, not unhappily, that his chief contribution to the military was made by playing in 180 or so ball games.

The Giants had made all sorts of joyous preparations for Willie’s return when he emerged from the Army in 1954. They even assigned Scout Frank Forbes to protect him from the perils of the big city. Forbes found Willie a room in a quiet home in Harlem. Once, when a damsel of doubtful reputation sidled up to Willie in a Harlem soda fountain, Forbes knocked a double chocolate ice cream soda into her lap to get rid of her. But such tactics, as it turned out, were unnecessary. Although Willie has since developed a taste for luxury, he was never one for living it up in the less respectable ways that attract some ballplayers. His idea of a jag was to go to two movies, one right after the other, and most of the time he was content to stay at home and curl up with a half dozen comic books. He still doesn’t smoke, and the only occasion, on record, when he took a drink was in 1951 after the Giants won the pennant. He drank a glass of champagne and was violently sick.

In 1956 Willie married Marghuerite Wendelle Kenny Chapman, a striking the handsome and chic woman two years his senior. Mrs. Mays has and 11-year-old daughter by one of her two previous marriage. When Willie went into a short-lived batting slump last year and entered a New York hospital for a rest and checkup, there were persistent reports that domestic difficulties were to blame for his troubles. Both Willie and his wife have denied the reports emphatically. Recently they adopted a baby boy, who has been named Michael. The Mayses seldom entertain and rarely go out in the evening. “Willie and I are not talkative people,” Mrs. Mays once explained. “We like to be by ourselves and mostly we stay at home. We like a good dinner, television or playing cards. Occasionally we go to a movie.”

Willie and his wife rent a furnished house in Phoenix during spring training. There was a brief flurry of headlines in the fall of 1957 when they bought a $37,500 home in a fashionable section of San Francisco. A few neighbors tried to stop the sale by raising the color bar, but the sale was completed without a hitch after the mayor of San Francisco, dozens of civic and social organizations and thousands of ordinary citizens sprang to Willie’s aid.

Nobody who has seen Willie in action needs to look at his impressive record to know that he is a great ballplayer. The only question before the house is, just how great is he? Willie’s good pal and mentor, Durocher, has never altered his belief that Mays is the greatest player alive. “I have never seen a ballplayer with his all-round ability, his instinctive baseball genius,” he claims. “There are only five things you can do to be great in baseball: hit, hit with power, run, field and throw – and the minute I laid eyes on Willie, I knew he could do them all. There is no player living today who can do all the things Willie can.”

Dapper Bill Rigney, who was one of Willie’s teammates in 1951, has long since confessed that he didn’t realize Willie’s full worth until he became his manager. “I thought I knew how good he was,” Rigney said, “but I realize now I knew nothing. This is like finding the Koh-i-noor diamond all over again.” Not long ago, as he stood behind the batting cage watching Willie joyously murder every ball that came within reach, Rigney blissfully went on record with the statement: “All I can say is that he is the greatest player I have ever seen. Bar none. When he’s around it makes me feel good just to walk into the locker room and start suiting up. I know then I have a chance.”

Veteran Giant Scout Long Tom Sheehan makes the historical point clear. “I’ve seen most of the great players, and there was not a one of them that could match Willie for all-round performance. That them all, I don’t care – Speaker, Cobb, Gehrig, Ruth, Traynor, Meusel. Then take DiMag, Williams, Musial, Mantle – or whoever else you can name. Sure they are good. Some of them are great. Some of them can hit and field. Some of them can run and throw. But Willie can do just about what they can in their special department and what’s more, he’s the only one of them who can do everything a ballplayer has to do.”

Recently, a visiting fireman, who knew somebody in the Giant hierarchy but little about baseball, was given a seat in the Giant dugout during the closing innings of an exhibition game. He sat there, smiling slightly, and obviously impressed to find himself seated next to the great Willie Mays. “Tell me,” he asked, “is it always this quiet on the bench? I thought there was a lot of chatter.”

Willie gave him a kind but amused look. “No, this is pretty quiet,” he said. “There’s a lot more talk going back and forth in a big game.”

“Do players work as hard in an exhibition game as they do in a regular game?” the stranger asked.

Willie smiled slightly. “I don’t know about the other players. I only know about myself.”

“Well, do you?”

Willie nodded slowly. “Yes I do. Don’t make no difference about what kind of game it is, I always work as hard as I can.” He sat musingly a moment. “That’s the onliest way I know,” he concluded, “I even know how to play ball.”