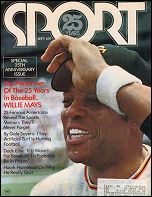

WHAT IS LEFT FOR WILLIE MAYS?

Wonderful Willie has done just about everything since

he came up in 1951. He simply wants to keep playing as only he can

play the game . . . and talks about another 10 years!

Complete Sports

1964 Baseball Annual

By Phil Pepe

Willie Mays plays baseball.

If you think that’s the all-time silly understatement, you’re right.

It’s an oversimplification and yet it’s not because there are few about

whom you can make that statement.

There are many baseball players. There are many who play at baseball.

And there are those, who like Roger Maris, who work at baseball.

But Willie Mays plays baseball. He does it because he likes it.

| True, he’s paid $100,000 a year to play the game because

he plays it better than anyone else around. But Willie would do it

for nothing because he likes it and, like a musician who enjoys his instrument,

it’s reflected in his performance.

That’s how it was for Willie at 19, that’s how it is now at 32 and that’s

how it will always be as long as he can pull on a uniform, drag his body

out to centerfield and use the instruments of his ability.

Fred Hutchinson, who manages the Cincinnati Reds, probably expressed

it best when he said, “I’ll tell you about Mays. It’s something everybody

overlooks. He enjoys his work.” |

There's

plenty left for

Willie

Mays. |

This is an attempt to explain why Willie drives himself relentlessly

through pain and punishment. Maybe it’s a complicated explanation

of what is really a simple matter – Willie Mays just loves to play ball.

When he plays, he’s the kid on the corner who just made the local Little

League team; he’s the high school sophomore who goes without lunch and

dinner to spend the day in the empty lot; he’s the rookie in spring training

who’s the first one out on the field and the last one in.

And when he tries to explain why he pushes himself until you’re sure

there isn’t an ounce of energy left in him, Mays explains simply, “I like

to play. Baseball has been good to me.” The truth is he has

been good to baseball.

It’s difficult to believe that a dozen years have passed since the day

in 1951 when the Giants called up the sensational rookie who was playing

at Minneapolis and who was to inspire them and help them write the Miracle

of Coogan’s Bluff.

The changes the years have affected on him are not noticeable to the

untrained eye. Physically there is hardly any change at all.

He has matured, to be sure. He is more at ease with people, more

poised at handling interviewers.

Watching him in the outfield, he is still the same 19-year old kid,

pounding his glove to make a basket catch, running out from under his cap.

The same kid with a zest for the game, an unbridled enthusiasm.

He is the kid, bubbling with delight after making one of his many spectacular

catches, then running full speed all the way into the Giant dugout right

into a thunderous silence.

“Did you see that, skip?” he squeals to Leo Durocher. “Did you

see that?”

Silence.

And Willie, turning on his pouting look of hurt, then catching on to

the idea and bursting into great peals of squeaky laughter.

“Willie,” says one veteran player, “brightens up any place he happens

to be. He’s a joy to be with.”

Watching him it hits you. Willie will always be 19 years old.

TEAM’S LEADER

One day last year, Alvin Dark, his manager, stunned his listeners into

shocked silence by announcing, “Willie is slowing up. You see it

on the bases. I think he’s a half step slower. You can’t detect

it on the field where he still makes those seemingly impossible plays,

but you can tell it when he runs the bases. Still I’ve always said

he’s the greatest player I’ve ever seen and now I think he’s better than

ever.”

That’s what maturity has done for Mays. Another thing it’s done

is give him a sense of responsibility to his teammates, his manager and

his fans. Not that Willie didn’t always have it, but now he feels

if the Giants don’t win it’s his fault because he is the veteran, their

leader, the guy they look up to.

That may explain why he picks himself up and goes out to play every

day even when it hurts him to do so. Even when he’s so tired, he

thinks he might not make it out to his position. He is driven by

obligation.

Since he came out of the army in 1954, Mays has played more than 150

games for 10 straight years and only Nellie Fox, among active players,

has topped that. Call it desire, call it enthusiasm, call it an obligation,

call it Willie Mays’ way. He knows no other.

Take the 1963 All-Star game in Cleveland. At the time of the voting,

Willie was hitting a mere .255, but his colleagues still picked him over

Vada Pinson, who was hitting some 60 points higher. Mays, in fact,

voted for Pinson and it embarrassed him to be selected.

In a game of Stars, Mays excels out of pride. He wants to be the

best of the best and he usually is. He played the game of his life

that day, probably driven by the desire to prove he belonged. The

only one he really had to prove it to was Mays.

Late in the game, he made one of his patented game-saving catches, a

back handed beauty on a drive hit by Joe Pepitone. As he reached

for the ball, he smacked into the wire fence with a sickening crash and

slumped to the floor. He lay there momentarily as the crowd hushed

and a half million San Francisco hearts sank into the Bay. Then in

a flash, he was up and sprinting into the dugout with a noticeable limp.

“I was glad to see him limp,” Dark said later. “When he limps

he’s in pretty good shape. He’s hurt if he just runs in. When

he’s hurt real bad, he don’t want nobody to know it.”

“It was nothin’, man, nothin’ ” Mays assured everyone. “I gotta

play tomorrow, I can’t hurt myself. It only hurt for a moment.”

For Willie, there is always tomorrow. That’s an important day

in his life.

“Whenever you’re in trouble,” Dark said, “he’ll find some way to get

you out. If you’re in China, he’ll show up pulling a rickshaw to

bail you out.”

It was just an exhibition game with half the season still before him,

but Mays played all out because it was a baseball game like any other and

that’s the only way Willie knows.

“It seems like I play the same all the time,” he said and he was right.

Spring exhibitions or World Series, Mays plays only one way – great.

Playing baseball is his joy, his pleasure and he’s happy to give you something

to cheer about.

At the time of the All-Star game Willie was hitting only .271 and there

were many who were beginning to count ten over him.

“I hope I’ll be around .300 somewhere,” he said. “I’m not concerned

about it. I resent the guys that say I’m finished. There are

guys older than me still playing and I can run as fast as I play defense.

I don’t worry about my fielding . . . it’s my hitting that needs points.

I ain’t no super star.”

HAD DIZZY SPELLS

And he ain’t no judge of talent, either, if he really believes that.

True to his word, Willie was right around there at season’s end.

He batted .314, hit 38 home runs and knocked in 103 runs.

Willie has given his fans anxious moments the past few years.

He hoped that would silence those who were counting him out.

There was one day in 1961, he suffered from dizzy spells, left the game,

then came back the next day to hit four home runs in a game. Willie

Mays doesn’t do anything in a small way.

The following year, he collapsed in the Giant dugout in the third inning

of a game against Cincinnati on September 12. The Giants were in

the thick of a pennant race, but Dark ordered

Mays sent to a hospital for a four day rest.

He came back to go on a typical Mays’ tear, 22 hits in 59 at bats, a

.373 average with eight homers and 18 RBI. In the first game of the

playoff with the Dodgers, he smacked his 48th and 49th homers to lead the

Giants, 8-0, over the Dodgers. After the game, he complained he was

tired.

“I don’t think there’s anybody in the world more tired than me,” he

said. “I’m so tired from playing all these games that sometimes I

can hardly stand up. Don’t ask me how I hit those home runs.

Maybe it’s instinct. Whatever it is, I just hope I can keep it up

for as long as it takes for us to win this thing.”

In the World Series, he again said he was tired. “Sure I’m tired,”

Willie told reporters, “but I’ll forget it. I got all winter to rest.

I’ll be tired when this thing is over.”

But after the Series, the Giants had Mays enter the Mount Zion Hospital

in San Francisco.

After three days of tests, Dr. Harold H. Rosenblum announced to a waiting

world, “there is no medical problem whatever. His condition is superior

to other men his age. He is in prime physical condition.”

“See,” said Mays with an I-told-you-so smile, “I knew what was wrong.

I was just tired, that’s all. We had a hard season all the way.”

But history repeated on Labor Day last year. Mays was hitting

against the Cubs, he fouled a pitch, slipped to the ground and suffered

from dizzy spells again. He went out of the game, but the next day

he was the first one out on the field, hitting fungoes, shagging flies

and making basket catches.

“I play all out whenever I play,” he explained. “That’s the only

way I know how to play. It’s harder for me to rest when a game is

going on than it is to play. I get restless.”

Now, everybody wants to know how long he can continue, driving himself

to the point of collapse year after year. Where will it end?

“I think I can play another 10 years,” Mays says like he’s hoping the

day will never come when he has to take off his uniform. It won’t

be easy for him, it’ll be less easy for those who have watched him.

But one thing is sure, as long as he is able to play, he’ll play the

same way he always has – hard, fast, spectacularly.

He couldn’t do it any way and still be Willie Mays.

Go back